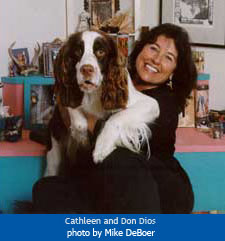

Cathleen Rountree, Ph.D. Cathleen Rountree, Ph.D.

This seventh-generation Californian and author of The Movie Lovers' Club: How to Start Your Own Film Group, is a globe-trotting film festival enthusiast, who pioneered the Movie Club concept in 1994. Passionate about World Cinema and auteur theory, Cathleen covers film festivals for various venues, and she is the author of numerous articles about the confluence of cinema, psychology, and cultural mythology for popular magazines and academic film and psychology journals. She regularly speaks at film, writing, and women's conferences in addition to teaching Writing and Multicultural Studies at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and a series of film studies courses: "Images of Women in World Cinema" (Iran, Latin America, Africa, Asia, and South Asia) and a How to Write About Movies course, at UCSC, Extension. Her nine books include: The Writer's Mentor: A Guide to Putting Passion on Paper, which focuses on the art and craft of writing, and the five-volume series of interviews and photographs with well-known writers, artists, and public figures--On Women Turning 30, 40, 50, 60, and 70. The Writer's Mentor, her coaching and consulting service, offers developmental and editorial assistance on fiction and nonfiction projects. She lives in a Northern California seaside community with Dios, her Springer Spaniel movie-loving companion and muse. Cathleen's first documentary feature film, Technicians of Imagination, based on her doctoral dissertation, is currently in development.

Cinema Magic: More Real than "Reel"

Since my early childhood movies have played a significantly tutorial, even pivotal, role in my life. People think I'm exaggerating when I tell them that-, from the age of four or five years old, movies served as my babysitters, best friends, teachers, and confidantes. I could even say that movies parented me. The cinematic gaze cradled me, enthralled me, became my eyes. Celluloid magic transmitted hope--and every other conceivable emotion--through its unique way of perceiving the world. Movies "taught" me about the human existential condition, about human drama, about love, about story.

Nor was I alone in this experience. This form of movie worship is exalted in Cinema Paradiso, Giuseppe Tornatore's unabashedly adoring memoir of the life-affirming--and -influencing--Sicilian village movie house, the parochial Paradise Cinema, he attended in his youth, where the projectionist Alfredo (who often speaks in film dialogue) initiates the cineaste-hero, Salvatore, as a child, into the magic of movies. Although overly sentimental for many, it still manages to stir any viewer who has a memory of childhood movie love. Nor was I alone in this experience. This form of movie worship is exalted in Cinema Paradiso, Giuseppe Tornatore's unabashedly adoring memoir of the life-affirming--and -influencing--Sicilian village movie house, the parochial Paradise Cinema, he attended in his youth, where the projectionist Alfredo (who often speaks in film dialogue) initiates the cineaste-hero, Salvatore, as a child, into the magic of movies. Although overly sentimental for many, it still manages to stir any viewer who has a memory of childhood movie love.

Just as they did for Salvatore, the temples of entertainment in Small Town, California, where I was raised, provided hours of sensation, safe refuge, and companionship for me, as an only child, and a form of inexpensive daycare that my divorced working mother could afford. Fifty cents for a double feature, plus a Flash Gordon serial, the current week's Newsreel, and a panoply of alliterative Looney Tunes (Bugs Bunny, Porky Pig, Daffy Duck) or Walt Disney cartoons (Mickey, Minnie, Donald, Pluto, Goofy) assured amusement and shelter for a minimum of four hours. Another two bits for a Mr. Goodbar and Dr. Pepper and I was set.

Summers were the best, because I didn't have to wait for weekends; everyday was Saturday. I had the option of sitting through one double-feature twice orŠ-my satchel of tuna sandwiches, small carton of milk, and apple under arm--walking the few blocks to another movie house and catching a second double-bill there.

I compulsively sat in the front row, even when the theatre was near empty. I could never get close enough and, like a homesick child, yearned to return to my true home: celluloid reality. My fantasy was to be enveloped by the numinous screen images, to forget every aspect of my small town existence, to be swept away on a sea of emotions and promise. Like Cecilia, Mia Farrow's character in Woody Allen's The Purple Rose of Cairo whose cinematic fantasy lover steps out of the screen and into her Depression-era life, I wanted to lose myself in the alluring glamour and palpable seduction of the movie lives before me. And I did. These "cinemyths" represented much more than fantasy: they were my present and my future. I compulsively sat in the front row, even when the theatre was near empty. I could never get close enough and, like a homesick child, yearned to return to my true home: celluloid reality. My fantasy was to be enveloped by the numinous screen images, to forget every aspect of my small town existence, to be swept away on a sea of emotions and promise. Like Cecilia, Mia Farrow's character in Woody Allen's The Purple Rose of Cairo whose cinematic fantasy lover steps out of the screen and into her Depression-era life, I wanted to lose myself in the alluring glamour and palpable seduction of the movie lives before me. And I did. These "cinemyths" represented much more than fantasy: they were my present and my future.

Years later, as an adult, I discovered that Allen's inspiration for Purple Rose had been the silent feature Sherlock Jr. in which Buster Keaton (also the director) did the opposite of Allen's characters: he walked into the movie screen. A brilliant metaphor for how films can eclipse every other aspect of the moviegoer's life and virtually become more real than, well, "reality." I was in cinephile heaven: "Where Happiness Costs So Little," reads the neighborhood theatre marquee in Walker Percy's novel The Moviegoer.

The Crest, Fox, Tower, Hardy's, and Warner Brothers Theatres offered me, my first jolt of Brando energy in Laslo Benedek's The Wild One and Elia Kazan's On the Waterfront, and I experienced my first crush on a matinee idol: James Dean in Elia Kazan's East of Eden and, later, Nicholas Ray's Rebel Without a Cause.

Brando, Dean, and later, Monroe, and the early roles they inhabited were powerful numinous forces and presences that usurped my consciousness and, on some level, helped form an impressionable young mind, unable to distinguish between real and "reel" life. The visual perception of these images comprised a soul experience. This "recognition" of something unspoken, even unknown, was a mystery at hand, the alchemical process of image becoming soul. Brando, Dean, and later, Monroe, and the early roles they inhabited were powerful numinous forces and presences that usurped my consciousness and, on some level, helped form an impressionable young mind, unable to distinguish between real and "reel" life. The visual perception of these images comprised a soul experience. This "recognition" of something unspoken, even unknown, was a mystery at hand, the alchemical process of image becoming soul.

As is so often the case with only-children of single mothers, I early on became my mother's companion. And as the cinema was one of her great loves, by the process of osmosis, it also became mine. I comprehended that watching movies together allowed us to communicate without speaking. Our shared experience permitted each of us to forget--at least for the duration of the films--our desolate lives. In less than a decade I would understand that the vocabulary of images knows no barriers to communication, the universal language of images is, what director John Boorman calls, an "esperanto of the eye."

Of course, we were not alone in this experience, as this is a phenomenon that affects the collective conscious and unconscious of all moviegoers, regardless of age, gender, socio-economic status, race, religion, culture, or geography: small town or major metropolis. Movies were a dynamic interaction within human psychology.

The cinema created a spiritual connection too. It was a centrifugal unifying force, a vortex of all experiences from all time, which contains all the contents of the psychic awareness of humankind. In the seen was also the unseen and, like the shaman's task, the cinema's mission was to transport us to other eras of experience and realms of knowledge. Movies were, and remain, an astonishing means of sharing in the human condition.

On her days off my mother took me to The Art House, an unoriginal name for the only local foreign film showcase. Like the town itself this movie house stood on the outskirts of an accepted social status. Only oddballs (of which we surely qualified) attended the art films shown in this square, squat stucco building that was painted powder blue on the outside and, like a shaman's cave, black on the inside. It was in The Art House that I was transported to a world, many worlds, really, that brought one-sided encounters with captivating cultures and, heretofore, unimaginable human predicaments (from Bergman and Fellini and Renoir) into the otherwise guileless, uninspired existence of a sheltered child's life. On her days off my mother took me to The Art House, an unoriginal name for the only local foreign film showcase. Like the town itself this movie house stood on the outskirts of an accepted social status. Only oddballs (of which we surely qualified) attended the art films shown in this square, squat stucco building that was painted powder blue on the outside and, like a shaman's cave, black on the inside. It was in The Art House that I was transported to a world, many worlds, really, that brought one-sided encounters with captivating cultures and, heretofore, unimaginable human predicaments (from Bergman and Fellini and Renoir) into the otherwise guileless, uninspired existence of a sheltered child's life.

The above-mentioned picture palaces held every bit of the mystery, magic, and manifest destiny that St. John's Cathedral held for me during the Roman Catholic Mass I attended each Sunday -- ritualized Catholicism was a set-up for the movies. Both were imaginal theatres of the soul, complete in their omniscience, and mysterious in their expressiveness, that afforded pilgrimages to a viewer's heart, mind, and body. Each had been designed and built during the 1920s and 1930s, when cinema began to take the place of religion and more people frequented movies each week than attended church services. They went to worship the new stars, while relinquishing the old saints.

These shrines to the moving picture were opulent and displayed mythic narratives and occult images on their four-storied walls and ceilings. Cosmic designs of planets and stars contributed to their sense of awe and grandeur and omnipotence. An ear-deafening Wurlitzer organ rising out of the bowels of an unseen underworld brought additional majesty and emotional resonance to the temple environment. Of course later, during my adult travels, I learned that these vast palaces had resembled gaudy versions of Gothic Medieval Cathedrals--Canterbury, Chartres, Cologne. These shrines to the moving picture were opulent and displayed mythic narratives and occult images on their four-storied walls and ceilings. Cosmic designs of planets and stars contributed to their sense of awe and grandeur and omnipotence. An ear-deafening Wurlitzer organ rising out of the bowels of an unseen underworld brought additional majesty and emotional resonance to the temple environment. Of course later, during my adult travels, I learned that these vast palaces had resembled gaudy versions of Gothic Medieval Cathedrals--Canterbury, Chartres, Cologne.

As in church, the pageantry of movie theatres included ceremony, ritual, trance induction, music, costumes, prayers, visions, oracles, divination, dream states, smoke and mirrors, magic and miracles, mythic storytelling, high drama, direct transmission and transformation, even contact with the dead. And the omni-present popcorn (with real butter) provided olfactory delight as well as a form of group communion.

At eighteen I traded in Catholicism for Cinema. Moving images, after all, were what "moved" me--what I worshipped, and the cinema continued to grow in importance in my life. No doubt, that from the earliest age, as the Mexican director Arturo Ripstein says through one of his characters (an ex-communicated priest, no less) in Divine (El Evangelico de las maravillas), "God [taught me] through movies."

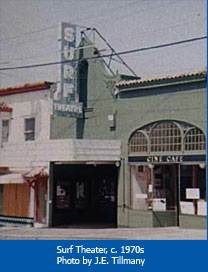

The summer after graduating from high school, I moved to San Francisco and began my cinematic education in earnest at Mel Novikoff's Surf Theater (where every summer I attended the Janus Film Festival and viewed all the foreign film classics--my first viewing of Truffaut's Les Quatre cents coup was a revelation) and the San Francisco International Film Festival, and later, across the Bay, at Tom Luddy's stellar Pacific Film Archive, near the U.C. Berkeley campus, which I attended.

My addresses, lifestyles, and professions have changed numerous times throughout the years, but my passion for movies has been a through-line in my life.

The Movie Lovers' Club is an opportunity to share my passion with you, and, in turn, for you to share your own movie love with your family, friends, new acquaintances, and right here on The Movie Club page, where you will find numerous options for sharing your illuminating insights, questions, and conversation.

See you at the movie club!

Home | About: Site Philosophy | About: Cathleen | About: The Book | Reviews: Current | Reviews: Archive

Purchase the book! | Festival Dispatches | The Movie Lovers' Club | Links | Contact

All text on this website copyright © 2006 Cathleen Rountree. All images and graphics copyright their respective owners, unless otherwise noted. Design by Jay Wertzler.

|